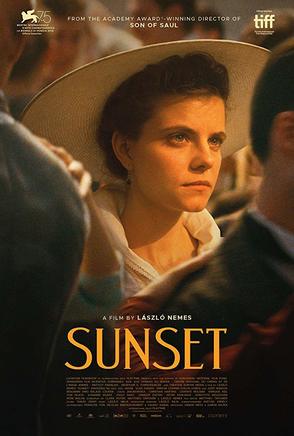

by Jelena VuckovicSince this is a Hungarian film, Hungarian names will be written in the order customary in the country, which means that last name comes before first. WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD  Immediately after the title card, this film feels a lot like the director’s first picture, Son of Saul. The camera, the score, the acting. Written by Nemes László, Clara Royer, and Matthieu Taponier, Sunset obviously took the recipe from the same cookbook. Melis László returns for the score, while Erdély Mátyás was the cinematographer on both of Nemes’ films. Kormos Mihály, too, reappears as the caretaker, and the lead is played by Jakab Juli, who was Ella in Son of Saul. At first, the similarities between the two films are glaring to the point of being offensive. And yet, as the film progresses, Sunset becomes so entirely different that comparisons to Nemes’ earlier film become obsolete. The fine dust of very-fin-de-siecle Budapest swarms around the characters in this fever dream of an adventure that initially looks a lot like Son of Saul but doesn’t taste like it at all. I watched this movie while sitting in a small, stuffy, Budapest theater—the kind now being driven out of business by multiplexes. The opening scene is a girl trying on hats in 1913 Budapest, and I get the feeling that because I speak the language I’m seeing a different Sunset from those who do not. Whenever I do glance at the writing on the screen, it seems better not to: the subtitles, to be brief, are terrible. Things that mean something like, “How long ago that was...” are translated as “Where is it?” Aside from that, I am pretty sure that the Hungarian-ness is palpable to all, if most do not know exactly what that is. Even the title, Napszállta, is an Easter egg for Hungarian people: it technically translates to “sunset,” but it is also an archaic term that some may recognize from the literature of the time, possibly a great-grandparent who liked to wax lyrical. But let’s get down to the actual film. We get to know the protagonist, a naive and more-curious-than-reasonable girl named Leiter Írisz (Jakab), as she appears at the millinery her parents used to own before they, and the store, perished in a fire and Írisz was shipped off to Trieste. She’s on a mission: a job at the hatmaker’s that bears her name. From her fine dress and manner, we can deduce that this is due to some sort of nostalgia, rather than to find gainful employment. So far so good, you would think, but things go sharply downhill from there. Not to reveal too much of the plot, Írisz is finally employed by the brutish boss, Mr. Brill (Vlad Ivanov), and soon finds out she has a brother. She then proceeds to purposely get herself into dicey situations involving various “randy” men, alone and/or in groups, and all of this is somehow related to the war about to start. Her motives remain murky, and often one is struck by a feeling that this girl suffers from some form of autassassinophilia, or the desire to seek out dangerous, possibly lethal situations. In contrast, the head milliner at the store is a strict, unkind, and a vitally important character named Zelma, played by Dobos Evelin with riveting grace and force. It seems obvious that in a scenario where we, the viewers, would have to name one of them as the victim, the choice would fall on Írisz. But this, like so many things in the film, is easier said than done. Sunset is not a story that moves logically from a to b or even has a clear plot structure. Very often, things seem to carry an underlying message, mysterious and unresolved, which may be frustrating for some but intriguing for others. For instance, there is a naked foot on a carpet—one simple moment that is still, perhaps, the most violent in this otherwise openly gruesome film. The image of the foot sticks with you, though it isn’t clear why. Anyone who has seen it will tell you that this picture is irritatingly ambiguous, both in plot and in moral, but in a way that entices and provokes. It may be hard to love, but Sunset is even harder to discount. Somewhere along the line, the search for the protagonist’s brother becomes unimportant, both to Írisz and to us: we are so close visually, not by choice but force, that we can’t help but become her. The camera rests on her face, or the back of her always tense neck, and the background is blurred so that we couldn’t break away even if we wanted to. Viewers have a lot of time to contemplate Jakab’s face and feel that it is one they won’t soon forget: both of the time and of the region, she was a perfect choice for the role. Her performance, which may seem inhibited and wooden at first, slowly becomes one thing above all: believable. Jakab’s eyes are often cast toward the ground beneath our sight, a telltale sign of reserve, fear, or shyness that belies her character’s bravery—or rather, lack of common sense. Írisz seems inappropriately undaunted by the fact that there is some dark plan afoot, where absolutely everyone is mean-spirited and whispering ominous things to her along her misguided journey down the rabbit hole. Still, it isn’t Jakab – it is Írisz who we feel should just get the hell out of dodge, out of this mess where it remains forever one against all and all against one. But she stays and uncovers a sinister ring of debauched, nefarious activity that is a metaphor for and reflective of a failing monarchy. The film obviously deals with an important time in history and draws parallels to the start of a war that changed the world, but to say that Sunset is a liberal interpretation would be an understatement. This, like most of its shortcomings, is not only forgivable but irrelevant. Sunset does capture the supposed zeitgeist of the period with authenticity – a feat that is not negligible. The set and costume design are breathtaking for the budget which, though many times that of Son of Saul, was still rather modest. It is almost painful how much effort is put into these parts of the production only to remain largely obscured. But it isn’t all in vain: the elegance of the frames and the people in them make the viciousness far more painful to witness. Many may see the similarities between Sunset and Nemes’ first film as a sort of cop-out. What makes a director’s style recognizable, after all, is not that the movies look the same. But Nemes, while deciding to use the same methods, made two movies entirely different from one another. This in itself is an achievement, if only to excuse any perceived laziness on his part. Sunset is shortlisted for an Academy Award in the foreign language category and, after seeing the rather piddling attempt of the German contender – by a director who has previously made one of the most fantastic films to ever come out of the country – I do not think Nemes’ sophomore effort is without a fighting chance. That being said, it’s clear that this film will be lost on many people, as is evident by the reviews (take the hilariously disparaging one by Jessica Kiang at Sight&Sound). But then, a lot of cult classics start out that way. Sunset is a Kafkaesque fever dream, or nightmare in plain English. This is a graceful film with horrible undertones, often so portentous it can become hard to bear – as nightmares often tend to. The first question that arose in my mind when the screen turned dark was whether this film had a feminist message. Nemes said in an interview that it was contemporary, in its way, which could be meant with regard to the political turmoil. But underneath that, is this a movie about a woman looking for her brother only to find her own strength? And then, just when I thought the movie had ended, well into a black screen, we’re suddenly in the trenches: wartime. There we see the protagonist, though she is disguised as a man so we’re not immediately sure whether we’re supposed to recognize her—unlike the other time she had tried to pass as male. The intellectual dilemma here, though, is that she would, in this scenario, be fighting for the monarchy. The very same thing she rose up against. Why? As I walked out of the little cinema into the night air of downtown Budapest, looking up at the buildings, appearing as if they were taken straight from the film’s set design, I felt glad Napszállta was made. - - - - -

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Copyright © 2018-19. Bread and Beauty. All Rights Reserved. Site Design by NightOwl.